套路(型)における最終目標

山口先生が、台湾の武壇で修行していた時代、劉雲樵大師から次の事を言われたそうです。

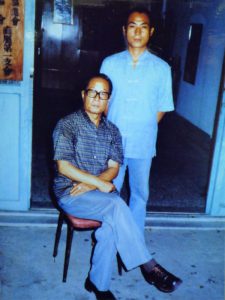

台湾の武壇で修行時代の山口先生と劉雲樵大師

拳法には3つの要素がある。一つは心身の鍛錬、2つ目が芸術性(内外面が一致した套路は、どこから見ても美しい)、3つ目が護身術という見方である。しかしどこに焦点を合わせて学んでいかなくてはならないかは、第一に上げられた心身の鍛錬が最も重要であることを強調された。

陳鑫も「拳は心の中にある」とはっきりと言っておられる。決して他と競うのではなく、自らの内面を追求して行かなければなりません。

太極道交会の目標である自己確立、自分というものをしっかりと見つめていく。そして自分という人格を完成させていく。そしてそれは太極拳運動(套路)を通じて、完成されるものであるということを信じています。

無功徳常精進